|

There

are perfectly good reasons for building an outdoor

shower at the cottage. It’s certainly cheaper than a

second bathroom, yet it provides a welcome

three-season facility when the cottage is overloaded

with visitors. You can wash after a swim (you’re

already wet, so why not get clean?) or after

finishing a particularly dirty task, and it’s by far

the best place to give the cottage dog a bath. It is

also easier to maintain than its indoor counterpart.

You could even argue that, with fresh air and a view

of the sky and trees above, you’ll be communing with

nature.

But let’s face it, there’s another reason we like

using an outdoor shower. It’s—just a little—naughty,

kinda like skinny dipping. You’re outside, the sun’s

shining, water’s involved, you’re naked, and someone

probably disapproves.

For some, a shower head and flat stones suffice, but

we wanted to build a shower that would provide that

sense of freedom while giving some privacy for those

who prefer not to bare all. We incorporated sliding

doors in the design. They’re less visually obtrusive

than hinged doors when open, and since they need no

clearance around them, the structure can be located

very close to trees. The shower is sited in a

secluded spot, so the cottagers plan to leave the

sliding doors open almost all the time, closing them

only when they have guests.

|

MATERIALS

All wood is cedar, except where noted.

8 4x4 x 8' (length may

vary according to terrain): posts

8 4x4 post caps

10 2x4 x 12': framing

2 2x6 x 16': headers,

dressing bench

3 2x6 x 10': cross

headers, corner bench, overhang support

320 lin. ft. 1x6 tongue-and-groove: walls

2 1x6 x 8': shelves

4 3/4x6 x 14' decking:

deck boards

3 3/4x6 x 16' decking:

deck boards, outer valance, doorstops

1 2x6 x 14'

pressure-treated spruce: rim joists

3 2x6 x 10'

pressure-treated spruce: joists

4 1x4 x 12' spruce:

temporary bracing

4 2x2 x 3' spruce stakes

8 1' x 1' patio stones

(you may need more)

HARDWARE

32 3/8" x 6"

galvanized carriage bolts, nuts, and washers

2.5 lbs #10 x 3!/2" deck

screws (beige)

1.5 lbs #8 x 3" deck

screws (beige)

2.5 lbs #8 x 2" deck

screws (beige)

50 #8 x 1!/4" screws

1 lb 2"

galvanized finishing nails

4 medium

T-hinges

2 small

pulls

2 72"

pocket-door hardware sets outdoor-rated wood

glue plumbing fixtures |

|

|

As with any project,

you could make changes to reduce the complexity and

cost, and to customize it to your requirements. We

included two doors, a luxury that works with the

traffic patterns at this cottage, but may not be

necessary at yours. Eliminate one door or the entire

changing area, if you don’t need them; make the

floor plan larger or a different shape to fit your

location. You could also adjust the height of the

walls to suit your family’s average stature and

desire for privacy— make it as open to nature as

modesty allows.

I used cedar for most of this project because of its

obvious natural appeal. But as most cottagers know,

it ain’t cheap! Pressure-treated 4x4s and deck

boards are an acceptable alternative, and untreated

pine tongue-and-groove for the walls will last for

years here, since it’s above ground and will dry

quickly after getting wet.

Before you build, note that the effluent from an

outdoor shower is considered grey water and requires

proper disposal. This wastewater is commonly handled

by draining it to either a leaching pit or septic

system. Check with your municipality regarding

building permits and possible restrictions such as

shoreline setbacks.

This is a relatively straightforward project, and

two moderately skilled DIYers with a little basic

plumbing experience should be able to knock it off

in a couple of weekends. The cost— mostly for the

cedar, which I warned you is not cheap—is about

$2,500, including the plumbing fixtures.

Choose your site

Is there an ideal place for an outdoor shower? In

most cases, you want a sheltered spot, because a

windy location will shorten the

I’m-comfortable-standing-outside-while-wet-and-naked

season considerably. Heavy winds will also require

setting the corner posts in concrete footings

instead of simply placing them on 1'-square concrete

patio stones, as I did. If you have neighbors, give

some advance thought to their sightlines: Lay out a

few boards on the ground to mark the walls and bang

a few stakes into the ground where the corners and

the edges of the doors will be. Then, stand inside

the shower area. You’ll be able to see what your

view of the lake will be and what your neighbors’

view of you will be—if you can see them, they can

see you. Moving the shower slightly, or even just

repositioning a door, can make a big difference.

Consider the plumbing, too—how near is the water

supply, and how easy is it to install a legal

drainage system?

The bare-bones skeleton

1. Start by leveling four patio stones for the

corner posts. (You may have to stack a couple to

help achieve that level base.) This structure

is small and rigid enough that a little winter

heaving won’t do any harm, so full

below-the-frost-line footings aren’t necessary

unless it’s in a very windy spot.

2. If there’s any digging needed for your drainage

system, do it now, before you start building

overtop.

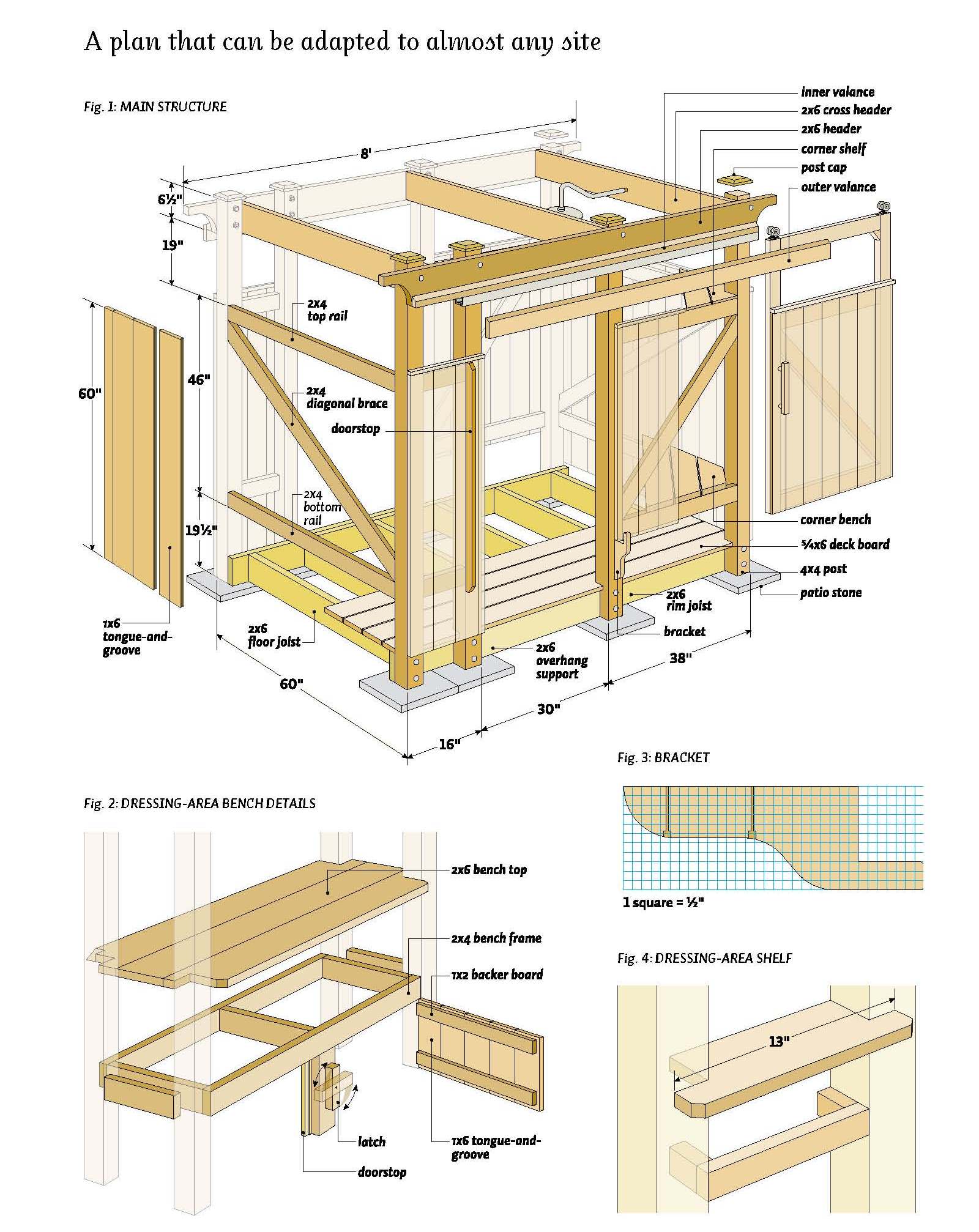

3. Cut and assemble the main elements of the end

walls— 4x4 corner posts, 2x4 frames, and

tongue-and-groove siding— in the ground (see

figure 1). I toe nailed the 2x4 frame pieces to the

posts with #10 x 3 1/2" deck screws and attached the

siding with #8 x 2" deck screws. Note that the

siding is longer (60") at both ends of the structure

and on the sides of the storage compartment; it’s

shorter (48") elsewhere. As well, position the

siding 1" above the top rails, because it just looks

better that way. Once the end walls are built, stand

them up and brace them.

4. Cut to length and scallop the ends of the two 8'

headers, then clamp in place on the posts. Cut two

2x6 pressure-treated rim joists for the floor

structure and clamp in position on the posts too.

Once the structure is plumb and square, and headers

and rim joists are positioned correctly, drill 4"

holes and bolt the clamped parts together (two bolts

per intersection). The lower set of bolts on the

headers must be flush with the surface, or the outer

valance won’t sit flat. You can either countersink

the bolts or over tighten them a bit to pull the

heads down.

5. Position four more patio stones for the other

posts. Bolt posts

to headers and rim joists. Trim posts to length, 1"

above headers. Screw post caps on top of posts.

6. Cut three cross headers and screw to the tops of

the posts, as shown in figure 1.

The floor

1. Cut 2x6 pressure-treated spruce joists to length

and attach between the rim joists with #10 x 35"

screws. Remember to install plumbing for the drain.

2. Cut nine deck boards for the floor from 5⁄4x6.

(Two boards have 2"-deep notches to fit around the

posts.) Fasten the boards in place with #8 x 3"

screws, making sure to leave even gaps (roughly

3⁄16"). To create access to the drain for

winterizing, here’s what I suggest: Locate the deck

board that’s overtop the drain. Cut out a section,

lining up your cuts over the centres of two adjacent

joists. Pre drill holes near these cuts in order to

avoid splitting the ends of the boards when you

screw them in place. In fall, unscrew this short

piece to fill the drain with non-toxic antifreeze

and plug it. As well, add an overhang support for

the edge of the deck board at each door: Sister a

30" length of 2x6 to the rim joist, between the

posts framing the door.

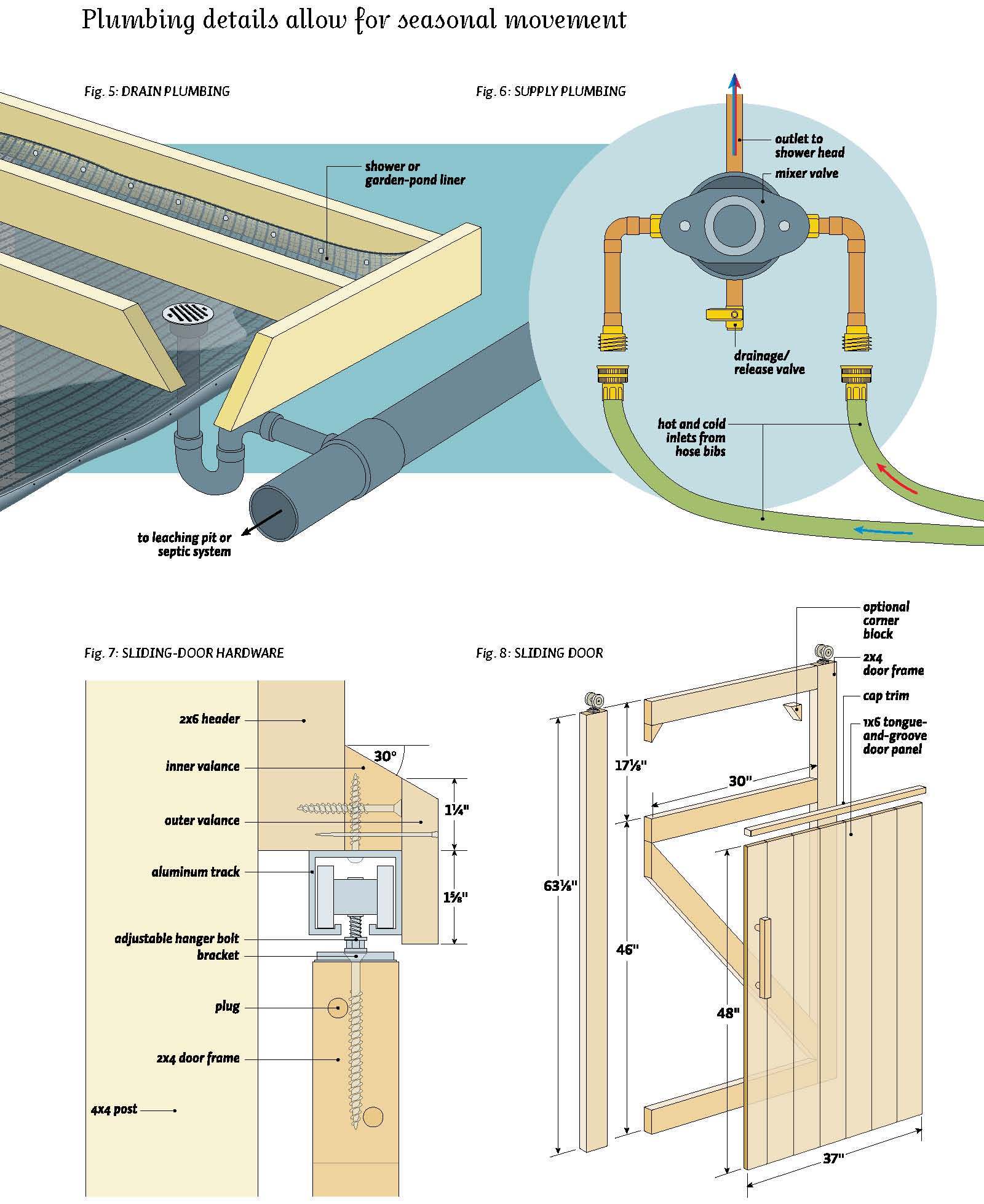

Side walls and doors

1. Cut and install the 2x4 frame and the

tongue-and-groove for the side walls.

2. Construct doors as in figure 8, taking care to

build them square. I used outdoor rated glue and two

#10 x 35" screws at each corner. Note that the two

screws should be offset from the centre line: one

screw 1" to the left, the other 1" to the right.

(This keeps them clear of the screws for the

pocket-door hardware.) You’ll have to countersink

them about 15". I filled the holes with pine plugs

because I like the contrast of pine and cedar. The

corner bracket is optional.

3. Rip lengths of tongue-and-groove to 6" x 8" to

make the cap trim for the walls and the tops of the

door panels. Nail in place, flush to the inside

surface.

4. Although the pocket-door hardware I chose is

meant for interior doors, it’s sturdy enough to use

outside. I did replace the screws in the package

with #8 x 3" deck screws to mount the supplied

brackets to the doors more securely.

Door details

1. From an 8' length of deck board, rip two inner

valance pieces as in figures 1 and 7. Trim to 7' and

mount with 2" screws and glue, flush with the bottom

of the headers. Rip the outer valance pieces from 8'

lengths of the 6" tongue-and-groove. Use finishing

nails and glue to attach them.

2. Attach the pocket-door track with the screws

provided. It should extend 1" beyond the post that’s

at the front of the bench. With help, hang the door

in the track. You may have to make adjustments so

the door is square in its opening, the cap trim

pieces on the door and wall align, and the door

slides freely. First, you can move the door away

from or closer to the structure: The bracket holes

are slotted for this tweak, but you’ll have to take

the door off the track first. As well, you can

adjust either end of the door up or down by turning

the hanger bolts. There’s a small wrench for this

purpose included with the hardware (try not to lose

it).

3. Rip 15"-wide doorstops out of 5⁄4x6. Cut to

length (4') and miter the ends. Close each door (the

2x4 frame should be parallel to the 4x4 posts) and

place the closed-position stop. A couple of 2"

finishing nails or clamps will hold the stop while

you screw it from the inside (for strength) with #8

x 12" screws. In the same way, open the door and

mount the open-position stop.

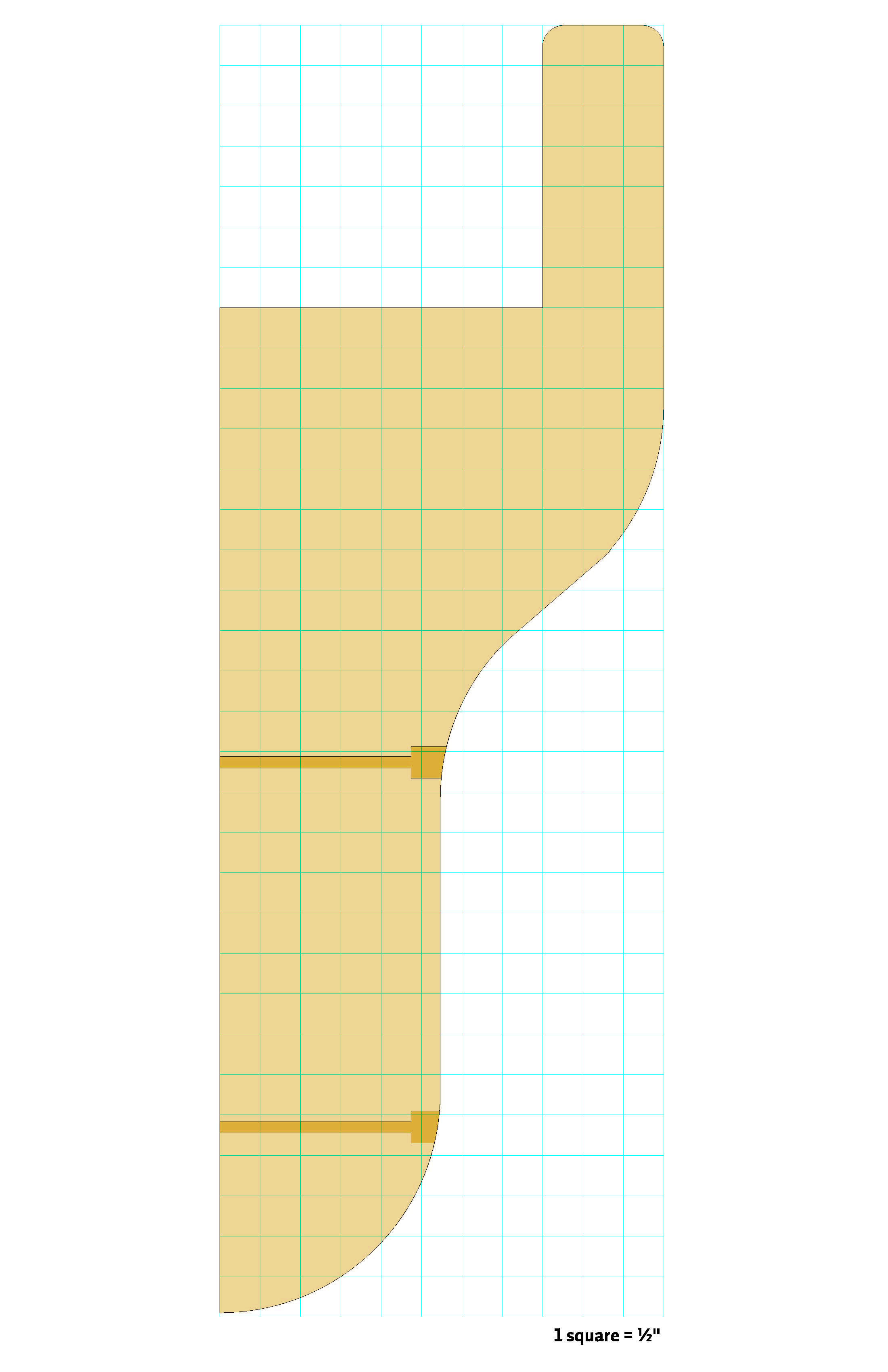

4. Add a bracket to prevent the bottom of each door

from swinging out as it’s pulled open or closed, as

well as to stop the door from rattling in the wind.

Cut these brackets from leftover 2x6. See figure 3.

Mount to the posts with 35" screws. It’s okay if the

doors rub a bit against the brackets, but they

shouldn’t bind.

5. Use corrosion-resistant handles for the doors or,

as I did, fashion some from 1" by 1" lengths of

scrap wood. Or make some out of other materials,

such as driftwood or small cedar branches. After the

winter, it’s possible frost heaving will shift the

shower; if the track isn’t level, the door may not

stay open or closed. Fortunately, the whole

structure is small and light enough that it can be

lifted slightly while you shim under the posts to

re-level it.

Benches and storage

1. Make the corner bench from three pieces of 2x6,

ends cut at a 45° angle. Mount each to the frame

with 3" screws, leaving about 2" between the boards.

2. The dressing area bench consists of three lengths

of 2x6 on top of a 2x4 frame (see figure 2). Cut and

install the 2x4s, then screw on the 2x6s, first

notching them to fit around the posts and the

diagonal brace.

3. Cut short pieces of tongue-and-groove for the

storage-compartment doors and attach with #8 x 12"

screws to 1" by 2" boards (ripped from a deck

board). I used T-hinges to hang the doors. Fashion a

simple doorstop and latch, and make your own pulls

from offcuts or driftwood, or use off-the-shelf ones

as I did.

Shelves

1. Above the corner bench, install a simple shelf.

Same idea as the bench, just smaller, using two

lengths of 1x6 cedar. Unlike the corner bench, I

notched the first board to fit around the 4x4 post.

Screw the pieces to the 2x4 top rail.

2. I added five small shelves (see figure 4) in the

dressing area, screwing supports (2"‑wide strips

ripped from 1x6) to the 4x4 posts, and then topping

with shelves cut from 1x6 and notched to fit around

the posts.

3. A few coat hooks, installed above the bench,

complete the shower construction.

Don’t stain, paint, or finish the wood—in an outdoor

shower, even the wood should be au naturel. Any

finish will be difficult to maintain; in time,

nature will provide a beautiful patina. You might

give the surfaces a scrub-down with a power washer

once in a while, but that’s it.

As a final touch, I looked for any corners, such as

those on the doorposts, that could make for a nasty

encounter with a naked body. I softened them with my

router and a 6" roundover bit, but if you don’t have

a router, plane and sand, or simply sand, these

edges.

|

Free

Outdoor Shower Wood Plans

(Right Click on Image, and Select View as

Image or Save As to See the FULL SIZE

Picture)

Free

Outdoor Shower Wood Plans

(Right Click on Image, and Select View as

Image or Save As to See the FULL SIZE

Picture)

Free

Outdoor Shower Wood Plans

(Right Click on Image, and Select View as

Image or Save As to See the FULL SIZE

Picture)

Water in

Supplying water to an outdoor shower

is a lot easier than many other

cottage plumbing projects for one

reason: access. Little, if any, of

the work is under the cottage, where

you’re inevitably pulling yourself

through dirt, commando-style, with

mere inches of headroom and unholy

hordes of bloodthirsty insects all

around.

Working on a flat, non-flammable

surface (i.e., not the deck), you

can solder all the parts together

for the mixer valve and shower head.

Start at the mixer valve, following

the instructions that come with it.

You’ll need a short stub of pipe

with a valve on the bottom outlet,

which usually connects to a tub

spout. Open this valve before winter

to drain the mixer valve so it won’t

freeze. The top outlet directs water

up to the shower head. The exact

fittings you need may vary with the

design of your shower head; staff at

a plumbing store can help you find

the right ones from among the dozens

of different bits and pieces

available. The two side outlets are

for hot and cold water coming in.

Here, I installed threaded fittings

to accept the garden hose I used to

convey water from cottage to shower.

Why a garden hose? The outdoor

shower is designed to accommodate

frost heaving, so I wanted to avoid

rigid pipe, which could break under

the strain of seasonal movement. As

well, hoses make prep for winter a

breeze; they can be removed and

drained in a matter of minutes.

At the cottage end, you need two

outdoor hose bibs (the taps that you

screw the garden hose into). You may

already have one for cold water, but

you’ll probably need to install one

for hot.

Water

out

Once water leaves the shower head

and touches you, it’s considered to

have cooties and must be disposed of

properly. The more technical term

for it is “grey water.” In some

circumstances, it can drain into a

leaching pit— essentially an

elaborate hole in the ground—out of

which it percolates to be treated by

soil bacteria. Leaching pits, a.k.a.

Class 2 Sewage Systems, are

regulated by building codes, which

sets out where they go and how they

must be built.

It’s often much less work to tie the

drain into the existing septic

system, especially if the shower is

near the cottage. A trap in the

drain will prevent sewage gases from

escaping. (While these gases aren’t

as dangerous emanating from an

outdoor shower as they can be

indoors, they are just as

unpleasant.) Each fall, you’ll have

to winterize this drain, by pouring

non-toxic antifreeze into the trap

and blocking the drain hole (to

prevent rain from diluting the

antifreeze).

But how do you collect the grey

water to get it into the drainpipe?

Some people install an acrylic or

fiberglass shower pan under the deck

floor. Another solution, which will

drain a larger floor area, is to use

a flexible, waterproof PVC shower

liner or even a garden pond liner. A

shower liner is usually used indoors

with a poured concrete pad to

prevent leaks. In this application,

you can simply attach its edges

(with roofing nails) to the joists,

forming a large catch basin. Insert

and secure a standard shower drain

in the liner and connect it to the

septic system or leaching pit. You

may have to dig a shallow depression

for the liner so the drain is at the

lowest point. |

|

|